CST Blog

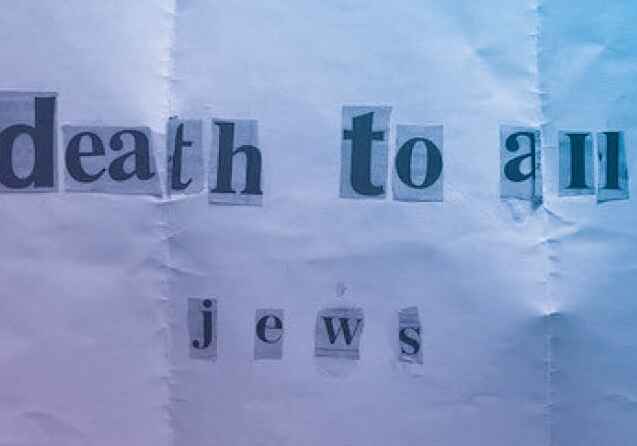

Using the law to halt Nazi slurs

17 July 2009

This is a guest post by Winston Pickett, via the Jewish Chronicle:

In assessing the consequences of antisemitic discourse, are some characterisations worse than others? Are some epithets more offensive due to the depth of the insult, the affront to memory or the power to malign the Jewish collective? If so, how should they be treated?

These questions go to the heart of the European Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitisms report, Understanding and Addressing the Nazi Card: Intervening Against Antisemitic Discourse. In seeking to answer the questions, authors Paul Iganski and Abe Sweiry have fashioned an indispensable tool for cutting through the conceptual fog that hovers over what could be called the discourse surrounding antisemitic discourse.

When the 2006 Report of All-Party Inquiry into Antisemitism flagged the use of words that vilify, demonise and demean Jews and Israel as a form of antisemitic discourse it provided a useful service for analysts, policy makers and politicians who sensed that something dangerous and Judaeophobic was taking place when Israel was compared to Nazis and the Nazi state. When the CST launched its own report last year that sought to red flag and quantify such antisemitic eruptions on an annual basis, a sense of QED seemed to be around the corner.

Yet critics and free speech purists cried censorship and claimed it was a way to silence legitimate criticism of Israel. They alleged it was fair criticism and that harsh words were sometimes needed to curb Israels excesses.

Meanwhile historians saw something more sinister at work: playing the Nazi card gives Holocaust deniers a cognitive pass, making what Anthony Julius calls fellow-travellers out of its users.

Even worse, it tacitly advances an insidious dialectic implying Jewish complicity, auto-genocide and the ineluctable conclusion that things would be better if a Jewish state did not exist at all.

In short, in the words of Iganski and Sweiry, a cul-de-sac of claims and counter-claims and a dead-end street with moral relativism the default victor in a standoff debate.

The ingeniousness of the authors analysis is that they seem to have cut through this quagmire. By labelling the Nazi card a speech act, the authors affirm the reality that such words and discourse are not simply dangerous. They inflict a singular pain one that is without parallel in history or emotional charge for the Jewish psyche. Further, it fits the same classification of hurt defined by law enforcement authorities and tagged as a hate crime component.

This is why it is vital to look at the reports recommendations when it calls on police and lawmakers to look more carefully at playing the Nazi card as a component of incitement or racial aggravation as a sign that antisemitism is more than the concern of a post-Holocaust traumatised minority.

Critically the report asks official bodies to accord playing the Nazi card with the same seriousness and sensitivity as the worst of racist epithets. How? By embedding interventions into codes of practice of umbrella authorities such as the University Colleges Union and Press Complaints Commission precisely those bodies that ideally seek to guarantee a certain level of civility in the maintenance of civil society.

Will it work? Even if their argument manages to pierce the its only hyperbole rationalisation and begins to gain traction then Understanding and Addressing the Nazi Card will have performed a valuable service by sending a clear signal to Jews and all ethnic minorities that hatred curtailed for one group helps curtail it for all.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025

CST Annual Dinner 2025

26 March 2025