CST Blog

Foreign Policy grievances arent always what you think

31 May 2013

After every jihadist terrorist attack in a Western country the political debate usually settles into a familiar pattern. Were the terrorists motivated by anger over Western foreign policy, or by a much more profound ideology that operates independently of any actions by Britain, or the United States, or any other Western nation?

It ought not to be controversial to argue that Western interventions in Muslim-majority countries influence the actions of jihadist terrorists: it would be strange if they didnt. However, in making this argumnent it is important to remember that jihadists idea of what Western foreign policy should look like is sometimes a long way from what Western policy ever could, or should, be.

Mehdi Hasan is a firm advocate of the foreign policy grievance theory and he set out his views in the Huffington Post this week, pointing out quite rightly that most jihadist terrorists justify their actions by reference to foreign policy grievances such as the current war in Afghanistan and the most recent one in Iraq.

But a simple model of cause-and-effect wont suffice to explain how these grievances translate into terrorism, because the overwhelming majority of British Muslims (and others) who feel intense anger about the deaths of foreign Muslims at the hands of British forces and our allies do not turn to violence as a remedy. There must be other factors that need to be present in order for a person to kill their fellow citizens in pursuit of this particular political aim. These include an ideology that persuades them that such violence is justified, morally, politically and (for jihadists) theologically; dehumanisation of the people they are going to kill; peer group support; and a whole range of other factors that relate to each individuals path to terrorism.

Hasan acknowledges this, writing:

It would be disingenuous of me to claim that foreign policy is the only factor driving radicalisation and extremism, just as it would be naive of me to pretend that terrorist attacks would cease overnight if the US, the UK and their allies stopped bombing, invading and occupying Muslim-majority countries. They wouldn't. There would still be hate-filled, messed up individuals, such as the group of British Islamists who plotted to blow up the Ministry of Sound nightclub in 2004 because of the "slags dancing around" inside, bent on acts of spectacular violence.

As Hasan rightly points out, foreign policy grievances did not begin with the 2003 invasion of Iraq. However, in doing so he inadvertently highlights an important flaw in the foreign policy grievance theory:

Ah, say the critics, but 9/11 preceded both the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan and Obama's drone war in Pakistan. They did - but the west's support for Israel's oppression of the Palestinians preceded 9/11. As did the murderous Anglo-American sanctions against Iraq.

The mid-1990s ought to have been the time when the power of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to mobilize the grievances on which terrorism relies was at its weakest. The Oslo Accords had been signed in 1993 involving Israeli recognition of the PLO; limited Palestinian self-governance had been established in Gaza and Jericho in 1994 for the first time in Palestinian history; and America was fully-engaged in a peace process that held out the promise of genuine progress.

The response to this peace process from terrorist groups was the opposite of what the foreign policy grievance theory might suppose. Hamas tried to destroy the peace process by sending suicide bombers to attack public transportation in Israeli city centres, popularising a form of terrorism whose legacy was felt so horribly in London and Madrid several years later. Palestinians linked to the secular Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine set off two car bombs in London. Algerian jihadists in France detonated a car bomb outside a Jewish school in Lyon. In Afghanistan, the networks of global jihad that coalesced around al-Qaeda were plotting terrorist attacks against Jews in Europe.

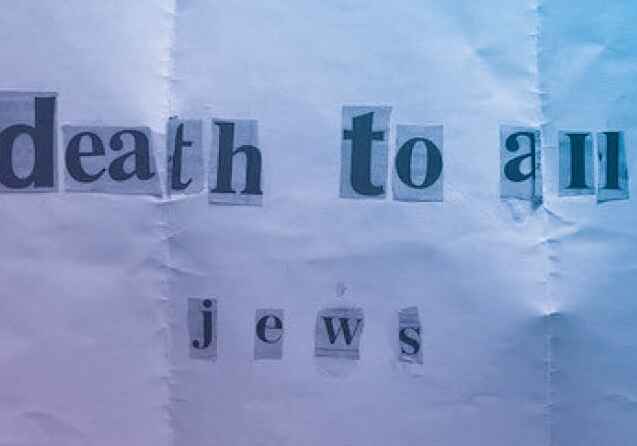

At the same time, British non-violent Islamist organisations launched a concerted campaign to fix Hamas as the political point of reference for British Muslims. One popular Muslim youth magazine, Trends, dedicated a whole issue to Hamas. The centrefold was a full colour poster of a map of Palestine including the whole of Israel superimposed with a picture of an AK-47 assault rifle. The Mawdudist Young Muslims UK declared: The decline of the PLO and the rise of HAMAS the Palestinian wing of al-Ikhwan al-Muslimun symbolises the end of a new era and the beginning of a new one. Hizb ut-Tahrir, then under the leadership of Omar Bakri Mohammed who would go on to form al-Muhajiroun, distributed leaflets on British campuses declaring Battlefield - The only place for Muslims and Jews.

The people who wrote Trends magazine were not the same as Hamas, which is not the same as al-Qaeda. But all three shared a political vision regarding what kind of Western foreign policy in relation to Israel/Palestine would have satisfied them. Islamist rejection of the Oslo peace process was uniform, because any deal that secured Israels permanent existence in the region was seen as an unacceptable betrayal. The only Western foreign policy that would have satisfied both the terrorists of Hamas and the campaigners of UK Islamism was a policy that aimed at Israels complete disappearance. Those who promoted this foreign policy goal - one which was never going to be conceded by any Western government - contributed to a grievance narrative (and therefore the potential recruitment pool) that could be exploited by terrorists, whether they intended to or not.

Anger over Western foreign policy does act as a proximate cause for jihadist terrorism in the West, and it is wrong to pretend otherwise. But while transitory political triggers change over time, the ideology and worldview that are necessary to develop that anger into a rationale for terrorism are much more profound, enduring and subversive. As their attitudes to the peace process of the 1990s show, Islamists, both violent and not, have their own agenda and their actions are not always merely reactions to Western policy; and when they do react, it is not always in the way that most people might hope or expect.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025

CST Annual Dinner 2025

26 March 2025