CST Blog

Inoculating Hate

8 January 2021

It’s a standard, and unfortunate, rule of thumb – that where there is heated discussion around Israel, antisemitism rarely seems to be far behind. It seems almost impossible to come across a thread or a Facebook post that broaches the topic sensibly and that doesn’t descend into arguments that flirt with age-old antisemitic tropes or that draw on Jewish suffering by labelling Israelis or Israel itself as Nazi-inspired.

This can be true for uncontroversial events to do with Israel, or even positive events: for example, CST’s 2019 report Hidden Hate: What Google searches tell us about antisemitism today revealed that antisemitic Google searches in the UK increased by 30 per cent in the days following Israel’s victory in the 2018 Eurovision Song Contest. What then of news articles that do cause controversy or that may be based on poor, inaccurate reporting? This is where the Observer and the website they share with their sister paper the Guardian come in, following last Sunday’s Observer piece alleging that Palestinians are being excluded from Israel’s COVID vaccine rollout. The article has received widespread condemnation, with many challenging some of the key premises within the article itself. A thread by CST’s Director of Policy, Dave Rich, about whether the article can be considered antisemitic can be read here https://twitter.com/daverich1/status/1346432346334093314.

The focus of this blog post however is not on the content of the article itself, but on some of the reactions underneath the article posted on the Guardian’s Facebook page. Antisemitism, like other forms of racism often involves some trigger event which may spark or lead to a racist response. One of the most well-known examples when it comes to antisemitism is conflict in the Middle East involving Israel, which often leads to a global spike in antisemitism against diaspora Jewish communities – something reflected in CST’s own antisemitic incident figures over previous years. These triggers can be large or small, positive or negative, and can (and do) affect Jews on a daily basis. It may be a road traffic incident, an argument between neighbours or, in this digital age, it may be an article to do with Israel, all potentially eliciting some degree of antisemitic response.

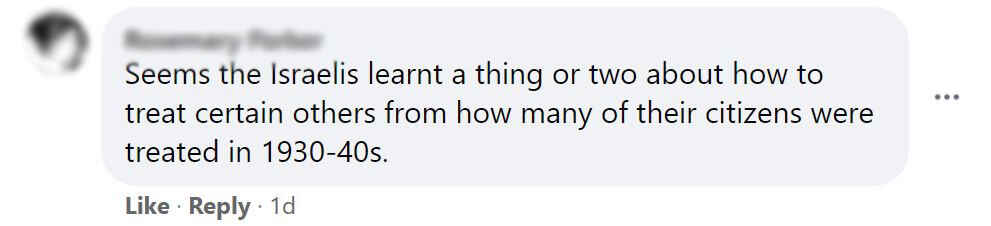

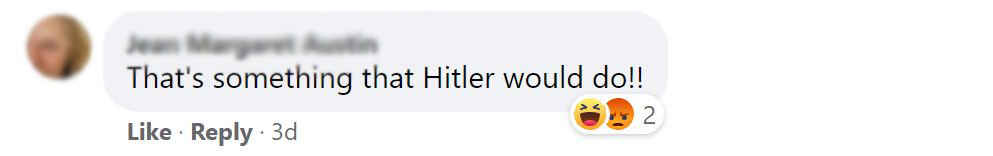

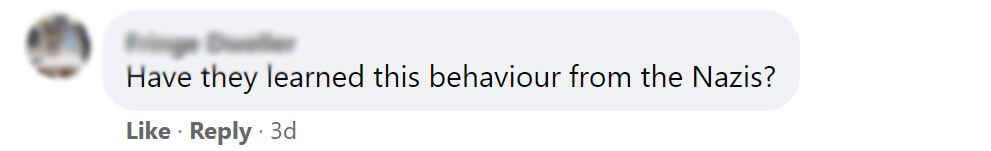

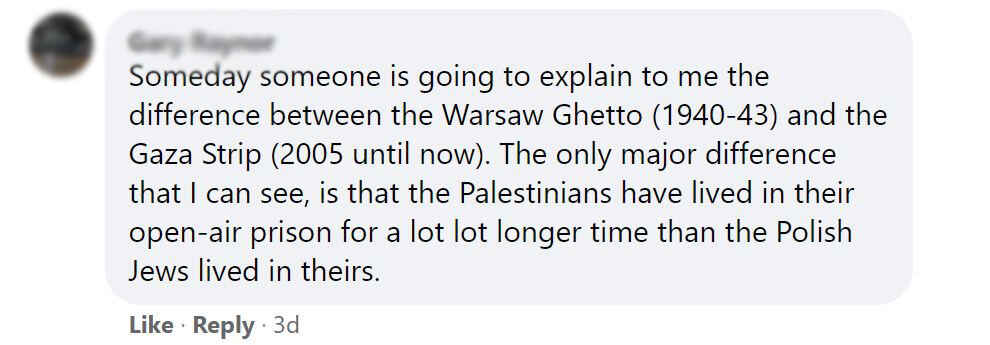

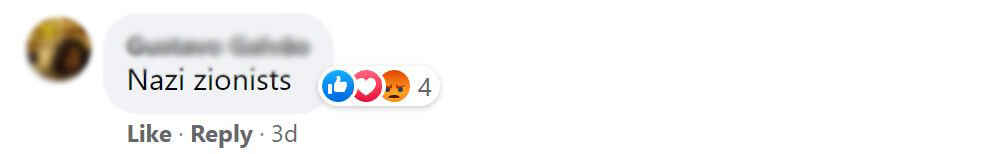

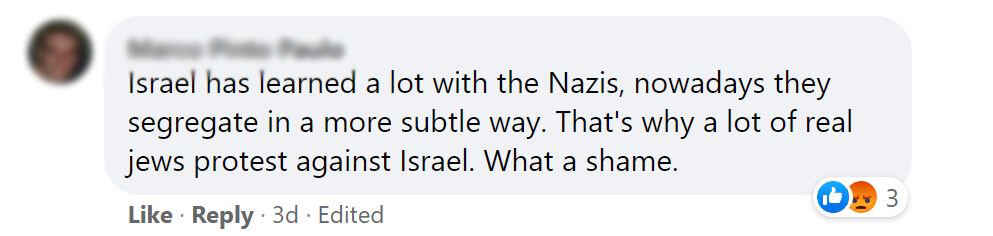

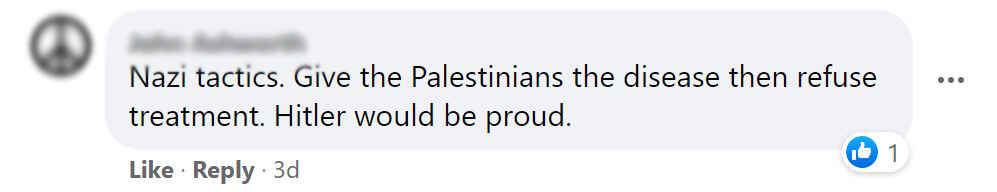

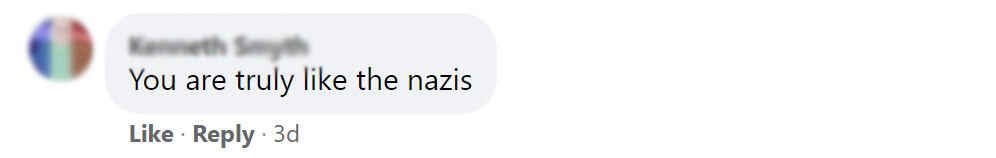

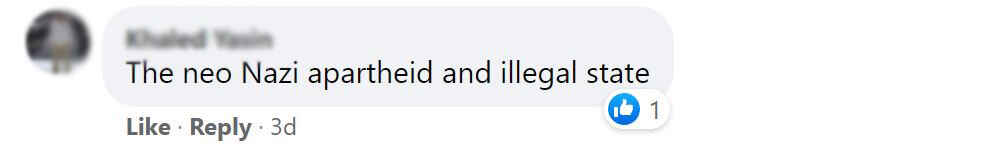

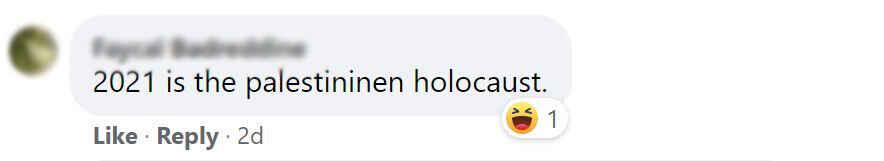

The responses underneath the article on the Guardian’s Facebook page are evidence of how online discourse in relation to Israel can sometimes lead to antisemitism. In the case of the Observer piece, this may have been heightened by the debate over the article's allegedly misleading nature. One of the prevailing antisemitic responses was to compare Jewish suffering at the hands of the Nazis during the Holocaust with how the Israeli state is acting today. This is fundamentally antisemitic as it weaponises the Jewishness of Israel as a means of attack. It also exploits Jewish suffering and pain to attack those who more often than not feel and understand the immense pain and loss caused by the Holocaust.

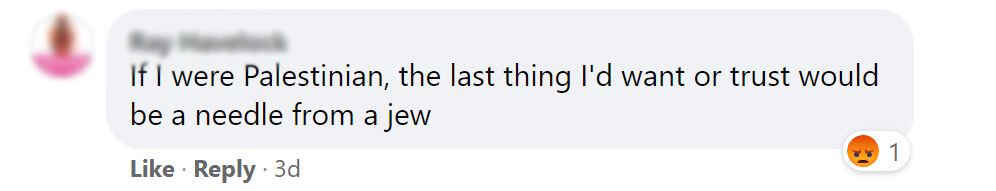

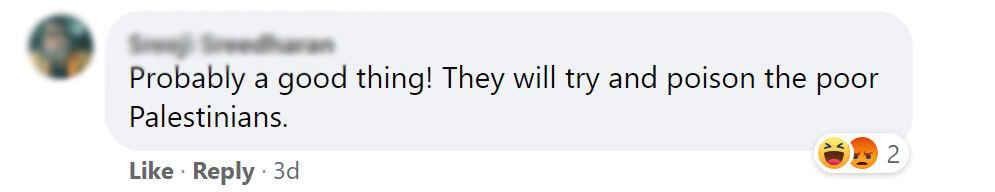

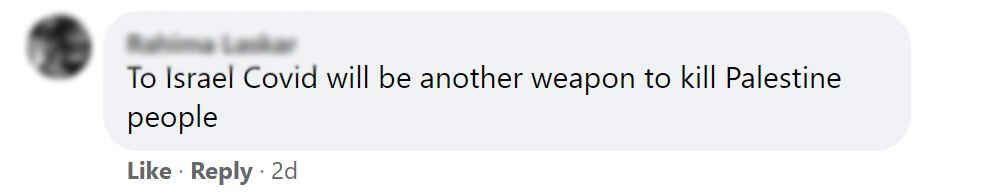

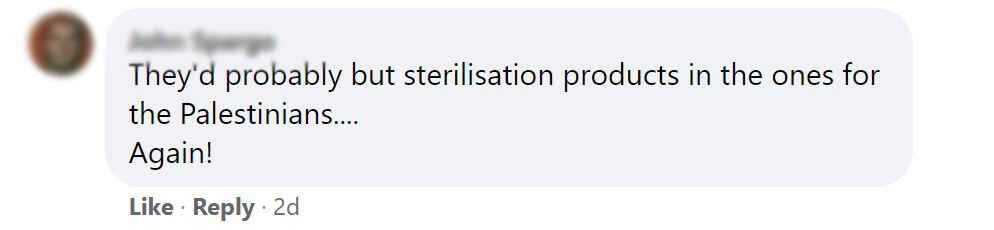

Other responses on the Guardian’s Facebook page are themed along the premise that Israel is deliberately not vaccinating Palestinians as a means by which to kill them, or that Israel would only vaccinate Palestinians in order to deliberately poison them. As documented in CST’s Coronavirus and the Plague of Antisemitism research briefing, this association of Jews with disease and infection is not original and draws on a long history of deep-rooted antisemitic tropes.

Antisemitic reactions to media content concerning Israel may be impossible to eliminate, but the very fact that we know to expect an antisemitic reaction places a burden of responsibility on those reporting on the issue, especially when that coverage is negative. In practice this means taking care when writing stories about Jewish-related issues, including on Israel, to be precise, avoid antisemitic tropes, and not to mislead. Just as one might expect readers of the Observer or the Guardian believe that sensitivity should be applied to media coverage on issues related to immigration due to the potential for racist backlash, the same should be the case when applied to Israel or other Jewish-related stories. This is not to say that coverage should be skewed, watered-down or minimised: simply that due care and attention should be applied.

Though the Observer and the Guardian cannot control how people respond generally to their content, they can certainly do this when that response is made on their public Facebook page. When media outlets started allowing readers to comment en masse on their own websites they quickly discovered a huge problem as many of those comments were racist, Islamophobic, antisemitic and misogynistic. Media outlets consequently invested a huge amount of time and effort into employing moderators to monitor and, if necessary, remove those comments. The Guardian’s Comment Is Free section was a good example of this, going from being one of the worst offenders to having one of the better moderation systems. Now it is social media that poses the problem for media outlets, with many opting to use platforms such as Facebook as a means by which to post their content. The Guardian must take responsibility for this content by removing antisemitic comments where necessary.

The irony in all of this is that the Guardian has recently become the platform of choice for campaigners who oppose the IHRA definition of antisemitism, because that definition takes account of the reality that there is sometimes a link between extreme anti-Israel animus and antisemitism. If the Guardian wants evidence for this link they could start with their own Facebook page: if you look hard enough, sometimes what you are looking for is right in front of you, or in this case directly beneath you in the comments section.

Read More

Love since 7 October

14 February 2025

Antisemitic Incidents Report 2024

12 February 2025

The Fall of Assad and the Zionist “Evil Plan”

8 January 2025