CST Blog

Counting hate crimes

5 August 2009

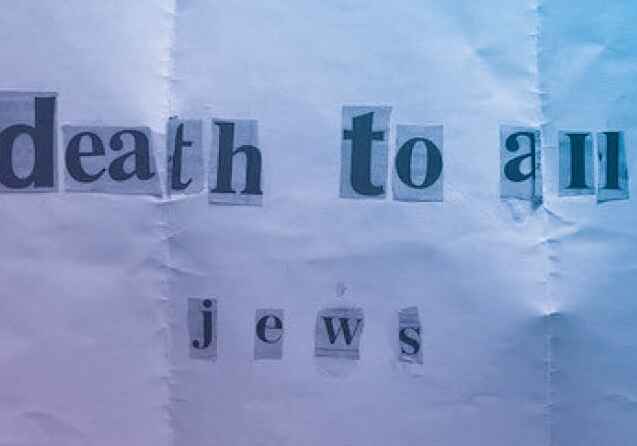

The Voice of America website has two interesting articles about the surge in antisemitic incidents recorded in many different countries, including the UK, in the early part of 2009, and on the need for stronger action by governments to deal with the problem.

The second article quotes the New York-based group Human Rights First:

Human Rights First's Paul LeGendre says these governments must do more to try to prevent future waves of violence targeting Jews and other religious and ethnic groups.

"Human Rights First has articulated a whole series of steps that governments need to be taking - not just responding to individual cases, individual outbreaks - but to develop adequate legislation, to develop adequate monitoring systems, to train police, to train the people who need to be reaching out to vulnerable communities when these types of attacks occur," LeGendre said.

...

LeGendre of Human Rights First says that of the 56 nations in the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, only one-quarter have systems in place to monitor hate crimes.

"There is really a huge data deficit which results in a lack of knowledge at the level of government," he said. "It results in not being prepared for backlash attacks like what we saw in January of this year, when governments are not aware of the extent of the problem, and are not making their police and not making resources available to those who need to respond to outbreaks of waves of such violence."

LeGendre says even fewer nations specifically monitor anti-Semitic violence. They include Austria, Britain, France, Germany and Sweden.

The European Union "Fundamental Rights Agency" says the lack of monitoring is a particular problem in countries that have small Jewish communities. Ioannis Dimitrakopoulos is the agency's head of research and data collection.

"There are a number of countries where we have no response regarding our efforts to persuade them to collect data," Dimitrakopoulos said, "and I would cite here countries such as Hungary, Romania, Greece, but also others, So there are many countries where things need to move along faster."

Efforts have been underway for many years to address the problem of poor, inconsistent or non-existent monitoring of antisemitic hate crimes, but developing consistent monitoring systems across different countries it is a long and difficult process. Some of the problems and obstacles are described in this paper, by CST's Michael Whine, as well as the different agencies and bodies trying to produce credible data. The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) and the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) are the two main organisations working on this problem, but both have met some or all of the obstacles described by Michael Whine:

- A lack of legislation defining violent hate crimes as an aggravating factor or as separate offenses. Currently, nineteen out of fifty-six states [in the OSCE] lack any legislation clearly defining hate crime. If hate crime is registered in general crime statistics it is generally impossible to extract those with a bias motivation.

- Lack of a central focal point for data collection. The absence of a national reporting center hinders the production of national statistics, even if there is localized reporting.

- Failure to record and classify the hate element of crimes. Only if the first responders to crime, the police, are given adequate training and provided with classification systems can they properly record hate crimes.

- Under-reporting. Vulnerable groups typically fail to report crime, and especially hate crime. In the case of anti-Semitic crime, the CST has found that Holocaust survivors in the Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) communities in London and Manchester have an innate distrust of the police, for obvious historical reasons (other NGOs elsewhere have found the same issues in dealing with Roma and Sinti victims). This is an issue that the CST has worked hard to overcome, but it generally requires central and consistent efforts to persuade disengaged, marginalized, or migrant groups to voluntarily interact with the police.

- Lack of funds and expertise for the purpose of establishing a monitoring and registration system. EU and OSCE states have not found it politically important enough to invest in data collection, despite having signed agreements to do so.

- Lack of disaggregated data. Without disaggregated data it is not possible to monitor vulnerable groups adequately. Only the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), French police, UK police (since April 2008), and some Canadian police forces do this adequately.

- Absence of a comprehensive data collection system. Even where hate crimes are registered, hate incidents with low levels of violence are often not reported to official channels and are therefore rarely recorded. The UK registers incidents as well as crimes; the FBI includes vandalism as well as physical attacks; and many NGOs report a much wider variety of hate incidents.

The 2009 FRA Annual Report found that only twelve EU Member States collect sufficient data on racist crime to conduct any sort of trend analysis. They are Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, and the UK. Of these, only six - Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK - collect sufficient data on antisemitic crime to conduct any sort of analysis. As the FRA website notes:

Data collection on hate crime is poor in most Member States, ranging from racist and related hate crime to other hate crimes, such as homophobic crimes. Insufficient or non-existent data collection leads to a situation where the true extent and nature of fundamental rights violations cannot be determined. However, understanding the nature and extent of fundamental rights violations is a precondition for developing effective, targeted policies at Member State level.

The first step to addressing any hate crime problem has to be the establishment of efficient, consistent and reliable data monitoring. Without this, it is difficult to create effective policing strategies or government policies. One reason why the problem of rising antisemitic incident levels in the UK is now quite well known, is because CST has been collecting, analysing and publishing the relevant data for many years. While the OSCE and FRA processes rightly focus on getting governments to meet their obligations in monitoring hate crime, they are also encouraging the establishment of community-based monitoring groups like CST. Their work can complement the official data, to provide a more rounded picture of the type of hate crime activity that is taking place. This contrasts with the problem of Islamophobic attacks against British Muslims: while there is a great deal of anecdotal evidence that this is growing, the lack of a central data collection point, beyond those incidents reported to the police, makes it difficult to fully analyse the scale and dynamic of the problem. In this light, Michael Whine's conclusion can be taken to apply to the monitoring of all hate crime, not just that against Jews:

The picture will be incomplete and impossible to analyze or adequately counter until central authorities collect and publish data routinely, consistently, and according to agreed and unified criteria. States' failure to implement the agreements that they have entered into requires Jewish communities also to monitor anti-Semitism. We would do so anyway, but we can make Jewish and state agencies work better by doing so according to internationally agreed norms. It also provides greater leverage to be able to negotiate around shared data and perceptions.

The first requirement on both states and Jewish NGOs is, therefore, that of objectivity. The ODIHR working definition of hate crime and the EUMC definition of anti-Semitism now provide objective criteria on which to base measurements.

The second requirement is that of methodology and consistency. Governments and their criminal justice agencies have undertaken to collect data, but many fall short in doing so. The ODIHR training for law enforcement officers and a planned program to train prosecutors to bring hate crimes cases to court will help to rectify the problem, but they cannot succeed before relevant legislation is enacted by states. Many have yet to pass laws which recognize the concept of hate crime, or which allow the courts to enhance penalties for hate motivation on conviction in the absence of specific statutes.

The third requirement is that governments should heed the advice of the international agencies and incorporate into their data the information provided by civil society organizations focused on combating hate crime. They should be under no illusion that official systems are capable of gathering evidence from all victims.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025

CST Annual Dinner 2025

26 March 2025