CST Blog

To Terrorise, Or Not To Terrorise

8 October 2010

The Independent newspaper (5 Oct 2010) carried a story that typifies the confusion and complexity of anti-Islamist terrorism strategies.

It concerns Mumbai-based Islamist preacher, Dr Zakir Naik, and has previously been reported elsewhere in print and at some length on the Internet. To summarise, Dr Naik is challenging the decision of Home Secretary, Theresa May, to ban him from entering the UK this June, when he was due to have addressed thousands of Muslims in London, Birmingham and Sheffield.

This was the first major test of the new coalition Governments attitude to UK admissions and exclusions; but Dr Naik claims that, prior to this, he had twice been approached by British security officials to help fight terrorism. As Dr Naik explained, this was to

co-operate with them [British security] to reach out to misguided young Muslims.

They said I would make an ideal envoy. I told them I would be happy to co-operate. Now after a change of Government, the attitude has changed. Only last year the Government wanted me to help tackle terrorism; this year they are calling me a terrorist.

The story looks set to repeat many of the themes that came to prominence in the infamous embrace by (then) London Mayor, Ken Livingstone of leading Muslim Brotherhood theoretician, Sheikh Dr Yusuf Al-Qaradawi. This controversy, in 2004, focussed media and public attention on the moral, political, and security challenges posed by the statements, activities and influence of overseas Islamist preachers upon British Muslim audiences. These issues then became matters of national priority after the London bombings on 7 July 2005.

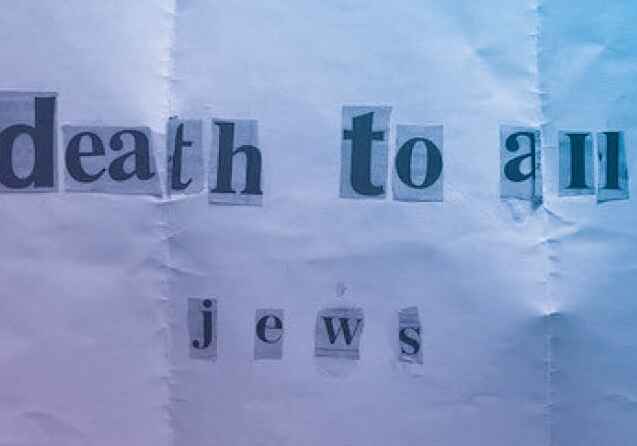

Naik and Qaradawi share many things in common. Both are leading Islamist preachers, heading Muslim research institutes and using television broadcasts to reach a wide audience. Both are on record as depicting Jews as enemies of Muslims and both have expressed support for (certain kinds of) terrorism.

If you find yourself in their line of rhetorical fire if you are, for instance, Jewish then you might well consider their presence in the UK not only contrary to the public good, but likely to increase the likelihood of their UK audience hating and attacking Jews. (Be they Jews from Britain, Israel, America, India or wherever.)

However, as Ken Livingstone still argues in the case of Qaradawi, both men are utterly sincere in their condemnations of terrorist attacks such as 9/11 and 7/7; and both men do have the credibility to turn some British Muslims away from terrorism. This is (one reason) why Livingstone embraced Qaradawi; and it is why Dr Naik appears to have been courted by Home Office security officials. It is easy to criticise such behaviour as being soft on Islamist extremism, but preventing mass casualty terror attacks (and the ensuing repercussions) is an enormous responsibility in hugely challenging circumstances.

The crucial paradox, of course, is that whilst Dr Naik and Dr Qaradawi both oppose terrorism, they also both support terrorism. It is tempting, yet ultimately misleading, to dismiss this contradiction as revealing hypocrisy, or lies, or doublespeak. The explanation is hidden in plain view, and is their interpretations of the words innocent and guilty (or, as in this case, anti-social).

For example, Dr Naik has been accused of saying that every Muslim should be a terrorist. The Independent reports his reply

I said every Muslim should be a terrorist to each and every anti-social element in society but no Muslim should ever terrorise a single innocent human being he [Dr Naik] insisted.

Dr Naik is President of the Islamic Research Foundation. Its website carries a press release that provides explanatory context and nuance to those of Dr Naik's statements concerning terrorism, Osama bin Laden and Jews that the Home Secretary took exception to. Naturally, the Foundation portrays Dr Naik in the best possible light, but it is the thrust of his messaging that matters and that invites the risk of British Muslims - at least those who see Dr Naik as an authority whose words are worth acting on - believing that they ought to be some sort of terroristic vigilantes, a revolutionary vanguard, terrorising "each and every anti-social element" until all of society is "innocent".

But who are these anti-social elements? Is it anti-social as described by the Guardian or the Daily Mail? By the British Nationalist Party or the Socialist Workers Party? By Dr Naik or Her Majestys Government? By the Koran (as interpreted by Dr Naik) or the British judicial system?

The Independent report further states of Dr Naik

While he is recognised as an authority on Islam, he has also earned a reputation for making disparaging remarks about other faiths, arguing that those "who change their religion should face the death penalty". He has also been filmed saying that "There are many Jews who are good to Muslims, but as a whole...The Koran tells us, as a whole, they will be our staunchest enemy.

So, even if (and it is a big if) we were to accept the notion that Dr Naiks presence can help prevent a terrorist attack against the general population of the UK, it evidently also runs the risk of increasing the threat to certain anti-social minority sub-groups in society (in this case, apostates and Jews).

The matter is made yet more important by Dr Naiks forthcoming appeal. He has been barred by the Home Secretary, but cites UK counter-terrorism experts in his defence. In other words, he will claim to have been barred for political reasons, and to be backed by those who are the real experts in counter-terrorism. He frames this case as the politicians versus the experts and cites civil servants in his defence.

This framing may well cause those British Muslims who follow and respect Dr Naik to further question and disregard the authority and legitimacy of the Government. If he loses, it will also lessen, for this audience, the credibility of the courts. This is the position into which Dr Naiks appeal and tactics have now led his supposed supporters at the Home Office.

It goes without saying that if Dr Naik, Dr Qaradawi and others were to actually promote, rather than oppose Al Qaeda attacks, then the terrorist risk would greatly increase. But equally, it goes without saying that opposition to Al Qaeda should be an absolute given as regards potential partners to help prevent terrorism and contest its drivers. Even here, however, Dr Naik equivocates. The Islamic Research Foundation press statement reads

Many journalists ask Dr Zakir Naik regarding his views about Osama Bin Laden. Due to the fact that he[Osama Bin Laden]has not been convicted in respect of 9/11 and as Dr Zakir Naik cannot verify the claims against him, he neither considers him a saint nor a terrorist.

Having failed to even acknowledge that Bin Laden is a terrorist, the press statement offers up the most miniscule of small mercies

There is not a single statement of Dr Zakir Naik after 9/11 in which he has praised Osama Bin Laden or supported his activities.

So much for "after 9/11", but what about before 9/11? The press statement actually includes Dr Naik's quote from a speech that included support for Bin Laden

...if he [Bin Laden] is fighting the enemies of Islam, I am for him. I dont know what hes doing. Im not in touch with him. I dont know him personally...If he is terrorizing the terrorist, if he is terrorizing America the terrorist, the biggest terrorist, hes following Islam...

It is not clear if the speech was in 1996 or 1998, but it may be viewed here (scroll in to four minutes for the Bin Laden section). The press statement defends this speech by stating

It is therefore not reasonable, in the light of Dr Zakir Naiks known views about 9/11 and all other atrocities such as 7/7 (London, UK) and 7/11 (serial train bomb blast in Mumbai, India) to link these manipulated and very old comments to recent world events.

Dr Zakir Naik has emphatically and regularly condemned any and all persons responsible for these appalling atrocities, killing innocent civilians.

This typifies why we must demand that opposition to terrorism is total, rather than conditional. Condoning terrorism always risks sowing the seeds for future "appalling atrocities". Subsequent condemnation is a very cold comfort indeed: especially when that condemnation cannot even bring itself to name the killers.

We live in a global village that is racked with many more conflicts than those directly involving Al Qaeda and its associates. As the world shrinks, so the British states political and moral opposition to those condoning - or equivocating over - terrorism should be getting louder and clearer. Special exception should not be made for those who would support (non-Al Qaeda) Islamist terrorism against Israel, or India, or Russia, or British forces serving overseas, or whatever arises tomorrow and the day after. Indeed, if anything, this is exactly where a consistent anti-terror discourse must be employed, because in our globalised world and diverse cities, the old geographical boundaries are increasingly irrelevant.

Tony Blair has stressed the need to defeat the narrative of extremists. There are those who would dismiss such logic simply on the basis of Blairs support for it: but it is not the invasion of Iraq that we are discussing. Rather, it is the overwhelming need to stress, without qualification, that to accept any ambiguity over terrorism overseas is to invite that terrorism onto our shores. This is the mistake that was made in the 1990s and it should be clear that where it failed once, it will fail again.

Theresa May has also been explicit on this, telling the Conservative Party Conference

Foreign hate preachers will no longer be welcome here. Those who step outside the law to incite hatred and violence will be prosecuted and punished. And we will stand up to anybody who incites hatred and violence, who supports attacks on British troops, or who supports attacks on civilians anywhere in the world.

We will tackle extremism by challenging its bigoted ideology head-on.

We will promote our shared values. We will work only with those with moderate voices. And we will make sure that everybody integrates and participates in our national life.

Staunch, unequivocal anti-terrorism messaging should be led by politicians of all parties, and fully backed by civil servants and security officials. Such a united front is paramount for engagement in the battle of ideas by which we either win or lose the right to define what words such as innocent, anti-social and terrorism mean here in Britain.

Opposition to terrorism that says little more than attack them, not us may pose as hard-headed realpolitik, but it also shares an alarmingly close resemblance to the path of least resistance, premised upon physical fear and moral weakness. Furthermore, this supposed realpolitik will always remain at the mercy of events and the whim of others.

Worse still, a counter-terrorism proposal based on this type of thinking leaves those in the firing line feeling especially isolated, vulnerable, and ultimately, disposable.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025

CST Annual Dinner 2025

26 March 2025