CST Blog

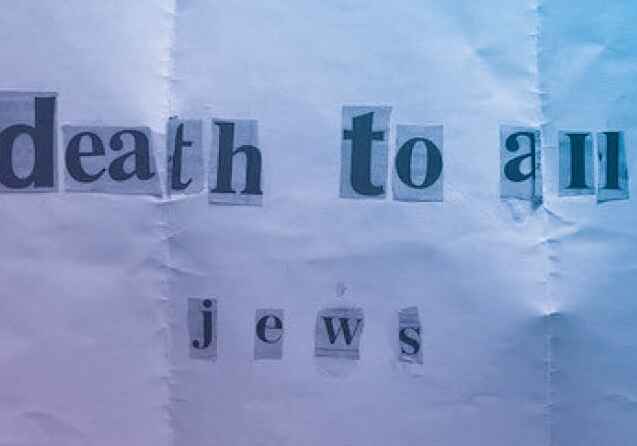

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Diplomatic Progress in Combating Antisemitism

27 October 2010

The Autumn 2010 edition of the Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, features a detailed article by CSTs Mike Whine on recent and contemporary international diplomatic efforts against antisemitism.

The extensively footnoted article is entitled, Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Diplomatic Progress in Combating Antisemitism and a full pdf of it may be accessed here via the CST website.

It begins as follows

During the late 1990s and forty years after the end of World War II, international organizations became aware of the recrudescence of antisemitism on a major scale. This was combined with a growing awareness that anti-Jewish sentiments were now emerging from new and different directions, although the traditional sources had not disappeared.

For Jewish organizations, this phenomenon was vividly highlighted by the events at the UN World Conference against Racism in Durban in 2000, where a noxious combination of states, mostly Middle Eastern and led by Iran, and many so-called human rights organizations, conspired to demonize Israel and Zionism, and to intimidate Jewish and Israeli delegates.

Whether this is new antisemitism or whether it is just the old anti-Jewish myths and tropes dressed in new garb is immaterial. Their increasing acceptance by new audiences, who have no memory of the Holocaust or the events that led to the creation of the State of Israel, as well as an increasing opposition to the USA and to globalization, pose significant dangers to Jews.

Against this background, governments themselves, spurred by some Jewish oganizations, came to realize that there was a need for action at the international level. Their interest was quickened in the aftermath of the intifada, and al-Qaidas attacks on the USA, when antisemitic incidents around the world rose alarmingly.

These developments led certain Jewish organizations to seek redress at the international level, and the resultant diplomatic offensive against antisemitism has therefore been carried out through the medium of intergovernmental organizations. Some organizations have played a greater and more effective role than others, but the initiatives have been more than declaratory. They involve programs at the grassroots level and within locales that have historically provided fertile territory for antisemitism.

The article then details the roles, successes and failures of numerous international organisations, including the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), its human rights affiliate, the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) and the key conferences in Copenhagen, Vienna and Berlin (in 1990, 2003 and 2004 respectively).

Parallel initiatives by the European Union and its associated bodies are also explained. Successes and failures are again noted, especially around the reports comprising Manifestations of Antisemitism in the European Union 20022003, published by the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC, but now renamed the European Union Fundamental Rights Agency). The mixed success of the EUs RAXEN (Racism and Xenophobia) network of national focal points is also shown; as are the origins and purpose of the EUMCs working guide definition of antisemitism. (The guide has often been a focus for those critical of international efforts to define and combat antisemitism.)

The EUs Common Framework Decision, scheduled for November 2010 will require all member states to legislate against the promotion of hatred (including antisemitism); and every four years, the Council of Europe's monitoring body, the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) reviews member states compliance with European and national legal instruments.

The United Nations is yet another international body with a mixed record on antisemitism, and its 2009 Durban Review Conference in Geneva attempted to move on from the ill-fated 2001 World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance.

Twenty-seven states have, thus far, signed the Stockholm Declaration (2009), described as among the most practical and long-lasting outcomes of international diplomacy, and one that stemmed from the concerns of statesmen rather than as a result of Jewish urging. This established an international taskforce to ensure that states recognize the magnitude of the Holocaust and its lasting impacts upon the Jews and others.

The article concludes with this assessment

It might be argued that ten years of diplomatic effort to counter antisemitism have been of little avail, given the dramatic increase in [antisemitic race hate] incidents and the deterioration in discourse, particularly following Israels 2009 Operation Cast Lead.

This would, however, miss the point. At the turn of the millennium, governments were reluctant to even recognize that antisemitism was once again growing. They could see antisemitism only through the prism of the far right, which was in retreat politically, and not through that of Islamism and the left, which were ascendant. They also underestimated the phenomenal power of information and communication technologies and the viral nature of internet social networking sites.

Since then, states have recognized the dangers to societies health by not combating the phenomenon, have agreed upon a common yardstick by which antisemitism can be defined and measured, and have recognized that it now also comes from new and different directions. Many states have also legislated against incitement of antisemitism in its various forms, including Holocaust denial. Those that have not yet done so, in Europe, at least, will have to do so by the end of 2010.

...Concern over growing antisemitism in Europe has been overtaken by concern for the mounting violence against Roma and Sinti, the massively under-researched violence against the disabled, and violence against Muslim communities. Progress in monitoring and combating antisemitism may therefore slow down as governments, their criminal justice agencies, and educational systems are put under pressure to adapt, innovate, and enlarge their work in a recessionary climate. However, the campaign against antisemitism should also progress as an element in the broader initiative of combating hate crime.

... The progress made in confronting and combating antisemitism since the 1990s has been neither continuous nor consistent, but without the determination of some governments, international agencies, and a handful of Jewish NGOs, the progress made thus far would not have been possible.

Given the manner in which the diplomatic initiatives have evolved, the onus remains on the Jewish (and other leading human rights) NGOs to ensure that progress continues to be made. In this task, they must work ever closer with governments, parliamentarians and international agencies.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025

CST Annual Dinner 2025

26 March 2025