CST Blog

Definitions of antisemitism: a quick guide

6 October 2016

One of the more curious things said by Jackie Walker, recently suspended by the Labour Party and removed as Vice-Chair of Momentum (although retained on its Steering Committee) for comments she made at a Labour Party training event on antisemitism, was that she hasn't "heard a definition of antisemitism that I can work with".

To aid Jackie, and for anybody else wondering about definitions of antisemitism, here is a quick guide to some of the definitions currently in use:

UK Government hate crime definition

The UK Government Hate Crime Action Plan 2016 defines a hate crime as follows:

Any crime that is motivated by hostility on the grounds of race, religion, sexual orientation, disability or transgender identity can be classed as a hate crime.

There are three categories of hate crime in legislation:

- incitement to hatred offences on the grounds of race, religion or sexual orientation;

- specific racially and religiously motivated criminal offences (such as common assault); and

- provisions for enhanced sentencing where a crime is motivated by race, religion, sexual orientation, disability or transgender identity.

The Action Plan also cites this definition of "hate motivation", taken from the College of Policing's Hate Crime Operational Guidance:

Hate crimes and incidents are taken to mean any crime or incident where the perpetrator’s hostility or prejudice against an identifiable group of people is a factor in determining who is victimised.

CST definition of an antisemitic incident

CST defines an antisemitic incident in the following way:

CST classifies as an antisemitic incident any malicious act aimed at Jewish people, organisations or property, where there is evidence that the incident has antisemitic motivation or content, or that the victim was targeted because they are (or are believed to be) Jewish.

CST divides antisemitic incidents into six categories: there are detailed descriptions of these categories in our leaflet, Definitions of Antisemitic Incidents.

CST deals with antisemitic discourse differently from incidents, and CST's Antisemitic Discourse Reports contain a selection of legal and non-legal definitions of antisemitism.

College of Policing Hate Crime Operational Guidance

The UK College of Policing, in its Hate Crime Operational Guidance (published in 2014), includes a definition of antisemitism that was previously developed by the European Union Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC), which has since been replaced by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). This definition, according to the College of Policing, does not replace the legal definition of a hate crime (as set out in the Hate Crime Action Plan, above) but "helps to explain some of the characteristics that may be present in antisemitic hate crime. These include circumstances that amount to hate crimes and those that are likely to be non-crime hate incidents." In other words, it is a practical guide to help recognise when antisemitism might be present, rather than a legally-binding definition. It reads:

Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.

Such manifestations could also target the State of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivist [sic]. Antisemitic hostility frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and is often used to blame Jewish people for ‘why things go wrong’. It is expressed in speech, writing, visual forms and action, and employs negative stereotypes and character traits.

Contemporary examples of antisemitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere could include, but are not limited to:

- calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews in the name of a radical ideology or an extremist view of religion

- making mendacious, dehumanising, demonising, or stereotypical allegations about Jews as individuals or the power of Jews as a collective, including especially, but not exclusively, the myth about a world Jewish conspiracy or of Jews controlling the media, economy, government or other societal institutions

- accusing Jews as a people of being responsible for real or imagined wrongdoing committed by a single Jewish person or group, or even for acts committed by non-Jews

- denying the fact, scope, mechanisms (eg, gas chambers) or intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of National Socialist Germany and its supporters and accomplices during World War II (the Holocaust)

- accusing Jews as a race, or Israel as a State, of inventing or exaggerating the Holocaust

- accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations.

Examples of the ways in which antisemitism manifests itself with regard to the State of Israel could include:

- denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, eg, by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavour

- applying double standards by requiring behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation

- using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (eg, claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterise Israel or Israelis

- drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis

- holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel.

However, criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic.

This definition is commonly known as the 'EUMC Working Definition'. It is also used by the National Union of Students as a practical guide to identifying antisemitism, a policy that was reaffirmed at NUS National Conference this year. A version of it was adopted by the US State Department in 2010. Despite what some critics suggest, it does not equate "criticism of the Israeli state with antisemitism": quite the opposite, it says that "criticism of Israel similar to that levelled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic."

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an alliance of 31 governments that promotes Holocaust remembrance and combats antisemitism. Its member states include the UK and come from Europe, North America and South America. In May 2016, IHRA adopted a "non-legally binding working definition of antisemitism" that is broadly similar, although not identical, to the EUMC Working Definition. It reads as follows:

Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.

To guide IHRA in its work, the following examples may serve as illustrations:

Manifestations might include the targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. However, criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic. Antisemitism frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and it is often used to blame Jews for “why things go wrong.” It is expressed in speech, writing, visual forms and action, and employs sinister stereotypes and negative character traits.

Contemporary examples of antisemitism in public life, the media, schools, the workplace, and in the religious sphere could, taking into account the overall context, include, but are not limited to:

- Calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews in the name of a radical ideology or an extremist view of religion.

- Making mendacious, dehumanizing, demonizing, or stereotypical allegations about Jews as such or the power of Jews as collective — such as, especially but not exclusively, the myth about a world Jewish conspiracy or of Jews controlling the media, economy, government or other societal institutions.

- Accusing Jews as a people of being responsible for real or imagined wrongdoing committed by a single Jewish person or group, or even for acts committed by non-Jews.

- Denying the fact, scope, mechanisms (e.g. gas chambers) or intentionality of the genocide of the Jewish people at the hands of National Socialist Germany and its supporters and accomplices during World War II (the Holocaust).

- Accusing the Jews as a people, or Israel as a state, of inventing or exaggerating the Holocaust.

- Accusing Jewish citizens of being more loyal to Israel, or to the alleged priorities of Jews worldwide, than to the interests of their own nations.

- Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor.

- Applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.

- Using the symbols and images associated with classic antisemitism (e.g., claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel) to characterize Israel or Israelis.

- Drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.

- Holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the state of Israel.

Antisemitic acts are criminal when they are so defined by law (for example, denial of the Holocaust or distribution of antisemitic materials in some countries).

Criminal acts are antisemitic when the targets of attacks, whether they are people or property – such as buildings, schools, places of worship and cemeteries – are selected because they are, or are perceived to be, Jewish or linked to Jews.

Antisemitic discrimination is the denial to Jews of opportunities or services available to others and is illegal in many countries.

What do Jewish people think is antisemitic?

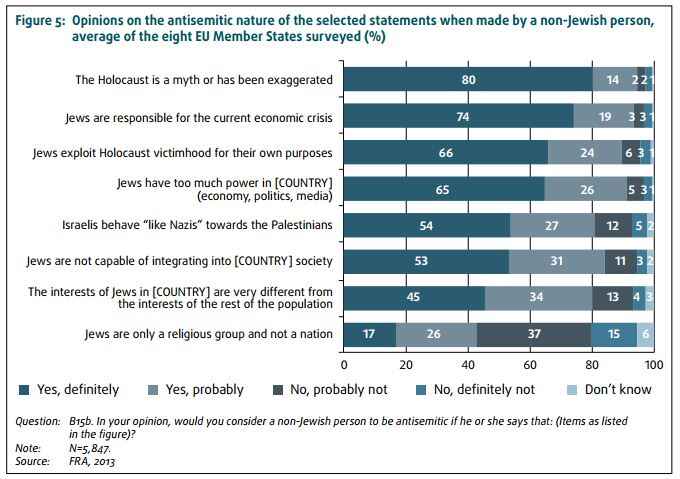

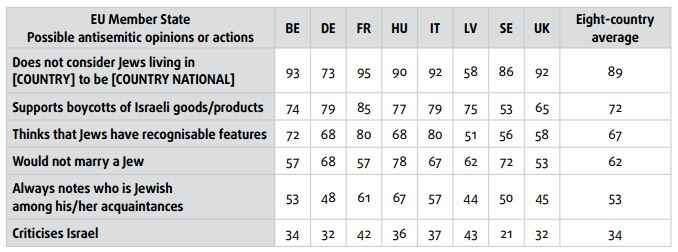

In 2013, the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) surveyed Jewish people in eight EU countries to find out their experiences and perceptions of antisemitism. They were asked about whether they thought certain statements and actions relating to Jews, Israel and the Holocaust are antisemitic. The results are in these two tables:

As these tables show, overwhelming majorities of Jews think that denying the Holocaust or accusing Jews of exploiting it for their own ends are probably or definitely antisemitic. The same goes for blaming Jews for the economic crisis, saying they have too much power and saying they can't integrate into their countries.

Where Israel is concerned, 81% of Jews in the survey think that comparing Israel to Nazi Germany is probably or definitely antisemitic. Nearly three quarters think that somebody who boycotts Israeli goods is probably or definitely antisemitic, but only 34% would say the same about somebody who criticises Israel.

Taken together, these definitions represent a remarkable consensus across 31 governments, the UK Police, the National Union of Students and the opinions of Jews in eight European countries. If Jackie Walker - or anyone else - can't "work with" these definitions, then instead of suggesting that these definitions are no good, perhaps it is Walker who needs to change her way of thinking about antisemitism.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report 2025

11 February 2026

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

CST Summer Lunch 2025

25 June 2025