CST Blog

Reactions to Engine of Hate report

15 August 2019

The angry reactions to CST’s recent report, Engine of Hate: The online networks behind the Labour Party’s antisemitism crisis, show exactly why such research is necessary.

The reactions denied what the report said, whilst demonstrating the behaviours that caused it to be written in the first place. Some might call that ironic.

Attacks have misrepresented what the report actually says. Similarly, CST has also been attacked and misrepresented.

CST expected these reactions. Nevertheless, the misrepresentations are worth noting and exposing. Unfortunately, doing so requires some length, so as the points can be explicitly demonstrated.

The report is entirely data driven. The number crunching was done by Signify, a data science company. Its findings are based on analysis of around 1.5m tweets over the past four years, and over 16,000 articles shared on social media that generated more than 10m social media engagements – tweets, retweets, likes, mentions and so on. The data has not been challenged.

36 key social media accounts are named in the report, which summarises them collectively as the “Engine Room”.

Misrepresentations of the report fall in three main areas:

- Claiming that CST somehow defined the 36 social media accounts as being antisemitic. We did not do this. We specified 12 of the 36 accounts as having “tweeted antisemitic content”.

- Claiming that CST somehow defined the 36 accounts’ overall narratives as being antisemitic. We did not do this. We stated their overall narratives and then, eight lines later, distinguished what we meant by the “antisemitic content” that was tweeted by the 12 accounts singled out for mention in this way. We then named the 12.

- Claiming that CST somehow defined generic pro-Labour Twitter hashtags as being antisemitic. We did not do this. The hashtags feature because the data shows their networking importance to the denials, anger and hatred generated by the 36 social media accounts; and to the antisemitic content tweeted by 12 of the accounts.

These misrepresentations are refuted within the body of the report, but are also made clear by the Executive Summary, from which the below three excerpts are taken.

The report did not accuse all 36 accounts of being antisemitic:

- “This report identifies 36 key pro-Corbyn Twitter accounts…that drive social media conversations about antisemitism and the Labour Party...Their status as Engine Room accounts reflects their general influence…and is not an indication about whether each account has itself tweeted antisemitic content…”.

The report distinguished antisemitic content from overall narratives:

- “All 36…at some point, tweeted content arguing that allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party are exaggerated, weaponised, invented or blown out of proportion, or that Labour and Corbyn are victims of a smear campaign relating to antisemitism…In addition, a third of these 36 accounts have themselves tweeted antisemitic content.”

The report did not define pro-Labour hashtags as antisemitic:

- “…[The 36] are all involved in, or connected to, Twitter networks that have used hashtag campaigns to target MPs or public figures because they have spoken out about antisemitism…These same accounts also drive generic pro-Corbyn, pro-Labour social media campaigns…”.

If you want more detail on the misrepresentations and what the report actually says, read on…

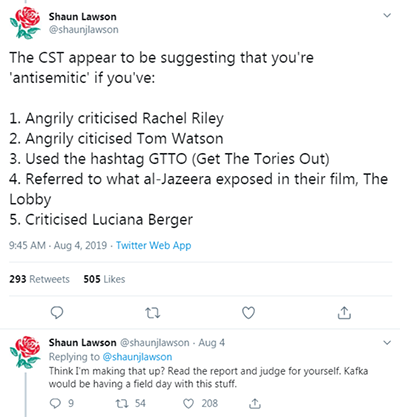

The most important starting point for the subsequent spread of misrepresentations, appears to be a series of tweets by Shaun Lawson. He made some very limited positive acknowledgements of its content, but those were overwhelmed by the rest of his claims.

Lawson tweeted:

“The report claims to have identified 36 Twitter accounts responsible for propagating antisemitism. And, to be fair to it, it does highlight at least some antisemitic tweets and accounts”.

As the Executive Summary shows, the report does not precisely say the 36 accounts were “responsible for propagating antisemitism” and it states that one third of the accounts “have themselves tweeted antisemitic content”. These points are repeated within the report.

Far more importantly, Lawson then went much further, stating:

“Yet it’s also done the most extraordinary thing. In effect, the CST have come up with a new definition of antisemitism. The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA)’s examples have nothing, absolutely nothing, on the CST.”

Then Lawson explains what he means by his bizarre allegation that CST has invented a new definition of antisemitism:

“The CST appear to be suggesting that you’re ‘antisemitic’ if you’ve: 1. Angrily criticised Rachel Riley 2. Angrily criticised Tom Watson 3. Used the hashtag GTTO (Get The Tories Out) 4. Referred to what al-Jazeera exposed in their film, The Lobby 5. Criticised Luciana Berger.”

Lawson asks: “Think I’m making that up? Read the report and judge for yourself.” On this we agree. Read the report. It is complex. It is nuanced. It goes where the data dictates. It does not redefine antisemitism.

Pages 10 and 11 of the report are “Definitions: What is antisemitism? What is anti-Zionism?”. These are entirely consistent with many previous CST publications. They are what we define as being antisemitic (not what we are accused of calling antisemitic). For all of the attacks made upon CST over the years, these definitions are hardly mentioned, never mind rebutted.

Lawson uses our report’s inclusion of generic pro-Labour hashtags so as to ridiculously imply that CST defines these hashtags as antisemitic. It is a preposterous suggestion, but it is a simple one: it satisfies an emotional and political need and so it has spread accordingly.

Page 19 of the report has a highlighted section explaining that #GTTO (Get the Tories Out) was used as a “baseline” precisely because it is a “generic pro-Labour, pro-Corbyn hashtag”, against which hashtags with specific relevance to antisemitism could be compared.

The reason #GTTO featured in the report was exactly because it is not related to antisemitism: and by comparing it to other hashtags, our data found that the same Twitter accounts driving generic pro-Labour hashtags also drive “campaigns relating to the denial of antisemitism and attacking those who complain about antisemitism.”

Let us repeat that. The report does not say that these other hashtags are “antisemitic”. It says that they relate to “the denial of antisemitism” and are used to attack “those who complain about antisemitism”.

Page 33 of the Report is entitled #Hashtags. It explains:

“The Engine Room group [the 36 accounts] are not only the strongest drivers of conversation around Labour and antisemitism, they are also major drivers of hashtags around a range of Labour-supporting topics.”

This section ends:

“Crucially, the same Engine Room accounts that drive generic pro-Labour hashtag campaigns also drive campaigns relating to the denial of antisemitism and attacking those who complain about antisemitism.”

Lawson’s tweet has also been used to allege that CST is defining as antisemitic, anyone who has “angrily criticised” Rachel Riley or Tom Watson about any random subject. This is also plain wrong. We analysed hashtags that were used to attack Riley and Watson specifically in response to their criticism of the Labour Party over its mishandling of antisemitism. Even then, we did not call these hashtags antisemitic per se: our report described them as “hashtags with particular focus on antisemitism relating specifically to the Labour Party”. Again, this was explained in the report sections that analysed those hashtags in detail (pages 34-42). Again, these explanations have been ignored, or perhaps misunderstood, by the report’s critics.

Pages 18 to 31 of the report detail the ‘Engine Room’ accounts. Again, we say that these are “amongst the most influential accounts on Twitter in engaging with online conversations about Jeremy Corbyn, the Labour Party and antisemitism.” In other words, not antisemitic by definition, but influential in online debates about Labour and antisemitism. The data behind this is explained on pages 13-14 and 18-21 of the report. Having identified these 36 influential accounts, our report deliberately states: “at this point, no analysis had been done to assess whether these accounts had tweeted antisemitic content. This is simply a list of the most influential accounts tweeting about Jeremy Corbyn and engaging with these five hashtags.”

Not only does the report repeatedly explain that the 36 accounts are not all antisemitic, it then states that 12 of the accounts “have themselves tweeted antisemitic content”. On page 20 it names these 12 accounts, further distinguishing them from the rest. Even here, however, CST does not state that the accounts or their owners are antisemitic. Instead, we say that they “have themselves tweeted antisemitic content”.

Despite all of this, there are activists now insisting that CST says all 36 Engine Room accounts are themselves antisemitic. Similarly, there are allegations that if you repeat the hashtags or arguments made by any of the 36 accounts, then CST will also accuse you of being antisemitic.

Lawson tweeted:

“Far and away the worst thing the report does is accuse those who’ve highlighted:

- That Labour’s ‘antisemitism crisis’ has been openly weaponised for political gain

- That a great deal of it is indeed a smear, because it’s not backed up by these awkward things called facts

…Of antisemitism. Outrageous and disgraceful.”

This is a ridiculous misrepresentation of what is explicitly stated in both the report’s Executive Summary and then on p.20 of the report, both of which literally include Lawson’s above points and makes clear that they have not been classified as antisemitic. Page 20 states of the “weaponisation” and “smear” narratives:

“[All 36 accounts] tweeted content arguing that allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party are exaggerated, weaponised, invented or blown out of proportion, or that Labour and Corbyn are victims of a smear campaign relating to antisemitism.”

The above point is even written in bold. Eight lines later, the report shows the distinction with what it defines as antisemitic content:

“Twelve accounts - a third of the total - have also, on occasion, tweeted content or used language that is itself antisemitic. This includes: allegations of a deliberate conspiracy by Israel, Zionists, or Jews to smear Corbyn, or other claims of a ‘Zionist’ conspiracy to influence British politics; pejorative reference to a ‘Jewish lobby’; denigration of UK Jewish organisations and activists as ‘traitors’ or as agents of a foreign country; antisemitic conspiracy tropes relating to the Rothschild family; equivalences between Israel and Nazi Germany; or other content that would be defined as antisemitic under the IHRA definition of antisemitism.”

The report then lists the 12 accounts that have done the above, that have “tweeted antisemitic content”.

We do not naïvely expect our words here, or in the report, to change the behaviour of our detractors. Still, it is remarkable to see what has been ignored, misunderstood and/or misrepresented from the report.

But then, the biggest lesson is surely to stop being surprised. This is how social media works. It narrows opinions, widens divisions, channels anger and ultimately fuels a hateful atmosphere. It is why CST commissioned the Signify research in the first place.

The report also sparked the usual accusations (not from Lawson) that CST is an arm of Israel, or whatever this month’s latest conspiracy accusation happens to be. It can be tricky to distinguish such hatred from antisemitism, but one such communication against the report described CST as a “tentacle”: language which we believe is loaded with antisemitic imagery and crosses the line from being mere hatred into actual race-hate.

CST is a UK Jewish communal body. Our staff, volunteers, trustees, and donors are British Jews. Our legitimacy, our consent and the demand for our work comes from the British Jewish community of which we are a part and which we strive to protect. We provide security for the overwhelming majority of UK Jewish communal sites. Anybody leading a Jewish communal way of life, to any extent, will have benefited from our work across Jewish communities throughout Britain. Our concern about Labour’s antisemitism crisis, and what helps drive it, is entirely focused upon what it means for British Jews and for the future well-being of our British Jewish community.

Read More

Antisemitic Incidents Report January-June 2025

6 August 2025

Love since 7 October

14 February 2025

Antisemitic Incidents Report 2024

12 February 2025